The ELEGY

Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard.

First Published 1751.

When Gray began writing the ‘Elegy’, he was in his mid-twenties and neither wealthy nor famous. On its publication, in 1751, he achieved an immediate poetic immortality that did not require embellishment, even from the greatest hero of his age.

The ‘Elegy’, published anonymously but immediately attributed to Gray in piracies and claimed for him in Richard Bentley’s landmark illustrated edition of Six Poems by Mr T. Gray (1753), has since been one of the most frequently reproduced poems. Within Gray’s lifetime, it was translated into French, German, and Latin. Since his death, Greek, Hebrew, Welsh, Armenian, Russian, and Japanese versions represent some of the more surprising forms in which the poem has appeared.

Multiple translations exist in several languages, notably Italian. Already anthologised in revolutionary America, it grew in popularity in the early Republic. Coupled with the work of Robert Blair and other graveyard poets, it was frequently included in collections. Its success has made it a regular subject for printers, illustrators (including photographers), and even binders, who were trying out new techniques or seeking to achieve striking effects, from the time of William Blake or Giambattista Bodoni, through the work of John Martin, Owen Jones, or Richard Lucas, to that of C.R. Ashbee, Julius John Lankes, Nicholas Parry, or James Brockman.

The ‘Elegy’ has appeared in all manner of formats and sizes and been sold cheaply and extremely dear. Much parodied, the poem has not been diminished by imitation. The full extent of its bibliography remains unknown.

Stoke Poges Churchyard, with the Tomb of Thomas Gray. Painted by William Augustus Barron. Collection: Pembroke College.

From 1742, Gray’s mother and her sisters lived at Stoke Poges, and his aunt, Mary Antrobus, was buried there in the churchyard of St Giles in 1749 (where Gray himself would later be interred). Gray had begun writing on the theme of mourning after the death of Richard West, in 1742, and worked on a more substantial and wide-ranging poem than the sonnet that he composed in memory of his friend (which was not published until 1775).

The final poem, in which Gray drew self-consciously on Dante and Petrarch, maintains a tension between the rustic moralism and native, Gothic virtue celebrated in many of its stanzas and the elevated sentimentality of its concluding epitaph. Rich with naturalistic references, it is in fact liberated from any location, and balances a sense of national pride with a strong and repeated call to virtue as embodied in the liberty of the village republic. As such, it draws as much on Spenser and Milton as it does on Catullus, Horace, Lucretius, or Theocritus.

-

The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

The lowing herd wind slowly o'er the lea,

The ploughman homeward plods his weary way,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

Now fades the glimmering landscape on the sight,

And all the air a solemn stillness holds,

Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight,

And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds;

Save that from yonder ivy-mantled tower

The moping owl does to the moon complain

Of such, as wandering near her secret bower,

Molest her ancient solitary reign.

Beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree's shade,

Where heaves the turf in many a mouldering heap,

Each in his narrow cell for ever laid,

The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep.

The breezy call of incense-breathing morn,

The swallow twittering from the straw-built shed,

The cock's shrill clarion, or the echoing horn,

No more shall rouse them from their lowly bed.

For them no more the blazing hearth shall burn,

Or busy housewife ply her evening care:

No children run to lisp their sire's return,

Or climb his knees the envied kiss to share.

Oft did the harvest to their sickle yield,

Their furrow oft the stubborn glebe has broke;

How jocund did they drive their team afield!

How bowed the woods beneath their sturdy stroke!

Let not Ambition mock their useful toil,

Their homely joys, and destiny obscure;

Nor Grandeur hear with a disdainful smile,

The short and simple annals of the poor.

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave,

Awaits alike the inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

Nor you, ye Proud, impute to these the fault,

If Memory o'er their tomb no trophies raise,

Where through the long-drawn aisle and fretted vault

The pealing anthem swells the note of praise.

Can storied urn or animated bust

Back to its mansion call the fleeting breath?

Can Honour's voice provoke the silent dust,

Or Flattery soothe the dull cold ear of Death?

Perhaps in this neglected spot is laid

Some heart once pregnant with celestial fire;

Hands that the rod of empire might have swayed,

Or waked to ecstasy the living lyre.

But Knowledge to their eyes her ample page

Rich with the spoils of time did ne'er unroll;

Chill Penury repressed their noble rage,

And froze the genial current of the soul.

Full many a gem of purest ray serene,

The dark unfathomed caves of ocean bear:

Full many a flower is born to blush unseen,

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

Some village-Hampden, that with dauntless breast

The little tyrant of his fields withstood;

Some mute inglorious Milton here may rest,

Some Cromwell guiltless of his country's blood.

The applause of listening senates to command,

The threats of pain and ruin to despise,

To scatter plenty o'er a smiling land,

And read their history in a nation's eyes,

Their lot forbade: nor circumscribed alone

Their growing virtues, but their crimes confined;

Forbade to wade through slaughter to a throne,

And shut the gates of mercy on mankind,

The struggling pangs of conscious truth to hide,

To quench the blushes of ingenuous shame,

Or heap the shrine of Luxury and Pride

With incense kindled at the Muse's flame.

Far from the madding crowd's ignoble strife,

Their sober wishes never learned to stray;

Along the cool sequestered vale of life

They kept the noiseless tenor of their way.

Yet even these bones from insult to protect

Some frail memorial still erected nigh,

With uncouth rhymes and shapeless sculpture decked,

Implores the passing tribute of a sigh.

Their name, their years, spelt by the unlettered muse,

The place of fame and elegy supply:

And many a holy text around she strews,

That teach the rustic moralist to die.

For who to dumb Forgetfulness a prey,

This pleasing anxious being e'er resigned,

Left the warm precincts of the cheerful day,

Nor cast one longing lingering look behind?

On some fond breast the parting soul relies,

Some pious drops the closing eye requires;

Ev'n from the tomb the voice of nature cries,

Ev'n in our ashes live their wonted fires.

For thee, who mindful of the unhonoured dead

Dost in these lines their artless tale relate;

If chance, by lonely Contemplation led,

Some kindred spirit shall inquire thy fate,

Haply some hoary-headed swain may say,

'Oft have we seen him at the peep of dawn

'Brushing with hasty steps the dews away

'To meet the sun upon the upland lawn.

'There at the foot of yonder nodding beech

'That wreathes its old fantastic roots so high,

'His listless length at noontide would he stretch,

'And pore upon the brook that babbles by.

'Hard by yon wood, now smiling as in scorn,

'Muttering his wayward fancies he would rove,

'Now drooping, woeful wan, like one forlorn,

'Or crazed with care, or crossed in hopeless love.

'One morn I missed him on the customed hill,

'Along the heath and near his favourite tree;

'Another came; nor yet beside the rill,

'Nor up the lawn, nor at the wood was he;

'The next with dirges due in sad array

'Slow through the church-way path we saw him borne.

'Approach and read (for thou can'st read) the lay,

'Graved on the stone beneath yon aged thorn.'

The Epitaph

Here rests his head upon the lap of earth

A youth to fortune and to fame unknown.

Fair Science frowned not on his humble birth,

And Melancholy marked him for her own.

Large was his bounty, and his soul sincere,

Heaven did a recompense as largely send:

He gave to Misery all he had, a tear,

He gained from Heaven ('twas all he wished) a friend.

No farther seek his merits to disclose,

Or draw his frailties from their dread abode,

(There they alike in trembling hope repose)

The bosom of his Father and his God.

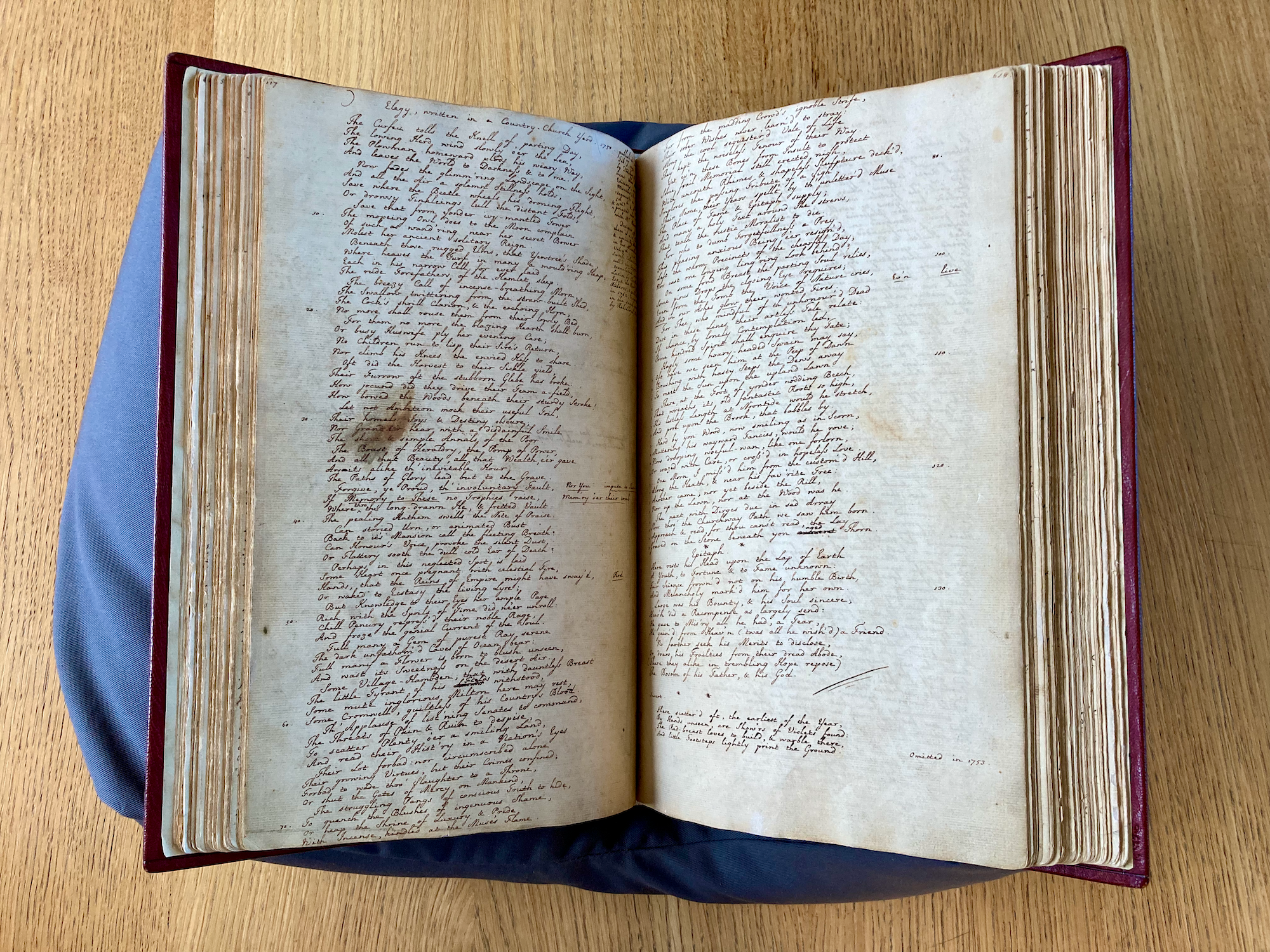

Thomas Gray’s Commonplace Book, Volume II (GRA/1/2). Elegy manuscript in Gray’s hand.

Pembroke College, LC.II.153: second edition of Gray’s ‘Elegy’: An Elegy wrote in a Country Church Yard (London: R. Dodsley, 1751).

Conceived in around 1742 and completed in early June 1750, the ‘Elegy’ was included in a letter written by Gray to Horace Walpole on 12 June 1750. It circulated widely in manuscript and, as ‘Stanza’s written in a country church-yard’, it appeared unauthorised under Gray’s name in The Magazine of Magazines on 16 February 1751. On learning this impending news, Gray urged Dodsley through Walpole to publish the ‘Elegy’ and the first anonymous edition, with the title prescribed by Gray, pre-empted the periodical’s publication by one day. Dodsley produced four further editions in the same year, with minor variations and additions. The second edition was really a corrected impression printed from standing type, and advertised on 25 February. Numerous manuscript versions survive, including the autograph sources for the poem at Eton College and in Gray’s commonplace books at Pembroke.

Peterhouse, Pet 473.c.72.: fourth edition of Gray’s ‘Elegy’: An Elegy written in a Country Church Yard (London: R. Dodsley, 1751).

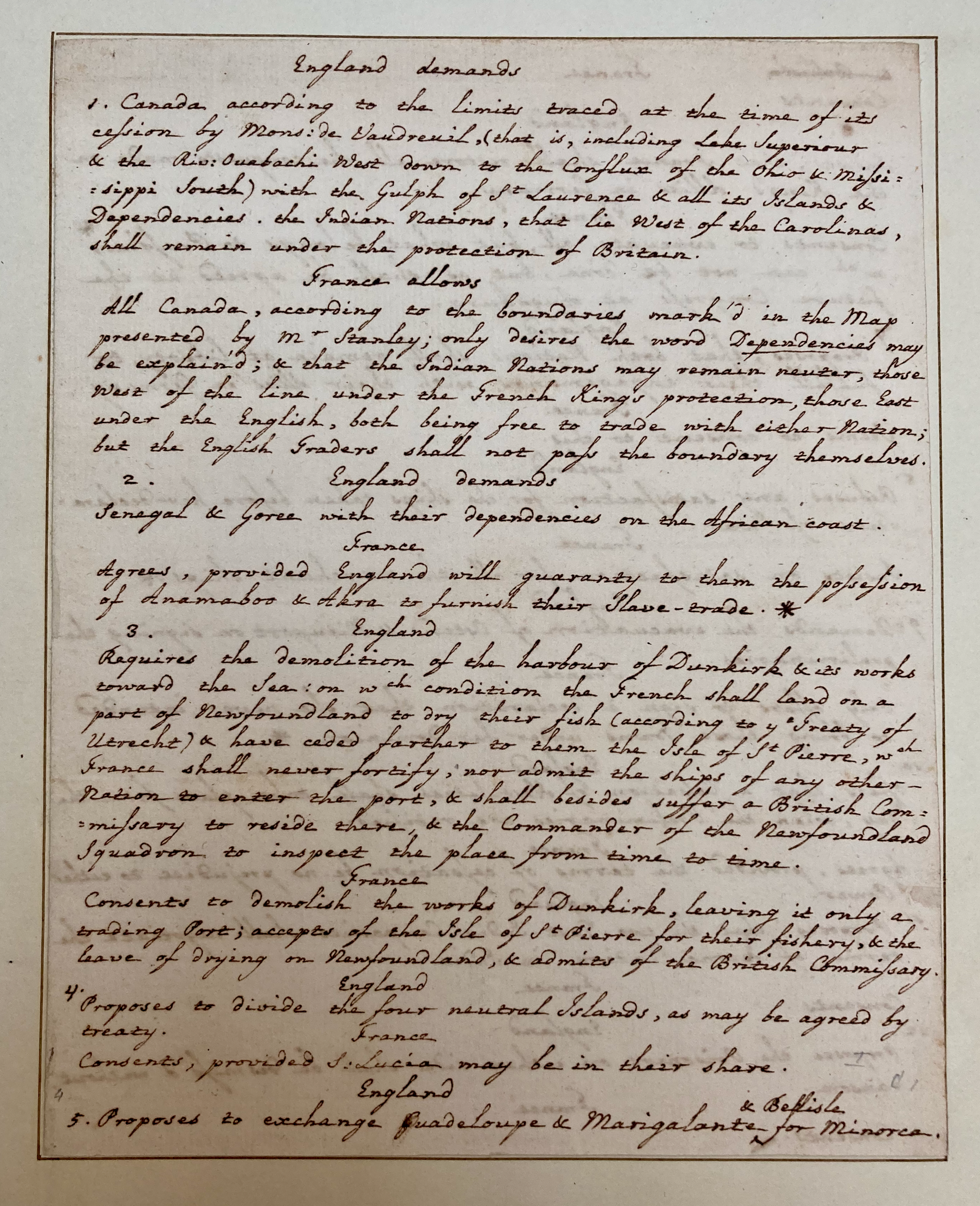

From Stoke Poges to the World

In a manuscript now at Peterhouse, Gray summarised the terms of the Treaty of Paris (1763) that concluded the Seven Years’ War, beginning ‘England demands… Canada… including Lake Superiour & the Riv: Ouabachi West down to the Conflux of the Ohio & Missisippi South… with the Gulph of St Laurence & all its Islands & Dependencies.’ Four years earlier, during the night before the decisive battle for North America, the British general, James Wolfe, reconnoitred Quebec from the St Lawrence river, repeating the lines of Gray’s ‘Elegy’ under his breath: ‘I would prefer being the author of that poem to the glory of beating the French tomorrow.’ Wolfe, whose death in battle was presaged in Gray’s line ‘the paths of glory lead but to the grave’, probably read the ‘Elegy’ when it was first published. His own copy (the ninth edition, published in 1754, and now in Toronto) is annotated alongside the line ‘A youth to fortune and to fame unknown’ with the question ‘Yet were he on this score less happy?’

Detail of ‘The Death of General Wolfe’, Painted by Benjamin West, 1770 . Collection: National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

Peterhouse, Ward Library, MS 971 Gray 3, in which Gray summarised the terms of the Treaty of Paris (1763).

‘A youth to fortune and to fame unknown’

General Wolfe in his copy of the Elegy.

‘The Elegy’ & its afterlives

When Gray began writing the ‘Elegy’, he was in his mid-twenties and neither wealthy nor famous. On its publication, in 1751, he achieved an immediate poetic immortality that did not require embellishment, even from the greatest hero of his age.

The ‘Elegy’, published anonymously but immediately attributed to Gray in piracies and claimed for him in Richard Bentley’s landmark illustrated edition of Six Poems by Mr T. Gray (1753), has since been one of the most frequently reproduced poems. Within Gray’s lifetime, it was translated into French, German, and Latin. Since his death, Greek, Hebrew, Welsh, Armenian, Russian, and Japanese versions represent some of the more surprising forms in which the poem has appeared.

Multiple translations exist in several languages, notably Italian. Already anthologised in revolutionary America, it grew in popularity in the early Republic. Coupled with the work of Robert Blair and other graveyard poets, it was frequently included in collections. Its success has made it a regular subject for printers, illustrators (including photographers), and even binders, who were trying out new techniques or seeking to achieve striking effects, from the time of William Blake or Giambattista Bodoni, through the work of John Martin, Owen Jones, or Richard Lucas, to that of C.R. Ashbee, Julius John Lankes, Nicholas Parry, or James Brockman.

The ‘Elegy’ has appeared in all manner of formats and sizes and been sold cheaply and extremely dear. Much parodied, the poem has not been diminished by imitation. The full extent of its bibliography remains unknown.

From 1742, Gray’s mother and her sisters lived at Stoke Poges, and his aunt, Mary Antrobus, was buried there in the churchyard of St Giles in 1749 (where Gray himself would later be interred). Gray had begun writing on the theme of mourning after the death of Richard West, in 1742, and worked on a more substantial and wide-ranging poem than the sonnet that he composed in memory of his friend (which was not published until 1775).

The final poem, in which Gray drew self-consciously on Dante and Petrarch, maintains a tension between the rustic moralism and native, Gothic virtue celebrated in many of its stanzas and the elevated sentimentality of its concluding epitaph. Rich with naturalistic references, it is in fact liberated from any location, and balances a sense of national pride with a strong and repeated call to virtue as embodied in the liberty of the village republic. As such, it draws as much on Spenser and Milton as it does on Catullus, Horace, Lucretius, or Theocritus.

Copies and parodies

Gray’s ‘Elegy’ was reprinted in the March issue of The London Magazine (pp. 134-5) and subsequently in a number of further periodicals.

Peterhouse, Ward Library, Pet.473.68: The London Magazine, or Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer (London: R. Baldwin, 1751).

Many parodies soon followed. In one ‘written in Covent-Garden’ : ‘St. Paul’s proclaims the solemn midnight hour,/ The wary Cit slow turns the master-key;/ Time-stinted ‘prentices up Ludgate scour,/ And leave the streets to darkness and to me…’

Peterhouse, Ward Library, Pet. 473.c.70: An Elegy written in Covent-Garden (London: J. Ridley [1771]).

Peterhouse, Ward Library, Pet. 473.A.25: John Duncombe, An Evening Contemplation in a College (London: R. and J. Dodsley, 1753).

A Cambridge parody began: ‘The Curfew tolls the hour of closing gates,/With jarring sound the porter turns the key,/ … Save that in yonder cobweb-mantled room,/ Where lies a student in profound repose/ Oppress’d with ale, wide-echos thro’ the gloom/ The droning music of his vocal nose.’ Duncombe was a Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and references some of his political and ecclesiastical patrons in the parody. The poem was, however, later reprinted as ‘an Oxonian’ parody of Gray.

Set to music

Pembroke College, 372.24: Thomas Billington, Gray’s Elegy set to Music (London: For the author, 1784).

The Exeter-born teacher of the harpsichord and singing master, Thomas Billington (1754-1832), composed this operatic setting of the ‘Elegy’, using music that he had composed as well as reworkings of the work of other composers. For most of his career, Billington taught and worked in London.

Billington’s notation for Gray’s Elegy.

Special editions

On loan from a private Sussex collection, arranged by Gorringes Fine Art Auctioneers, Lewes, East Sussex: Thomas Gray, Elegy written in a Country Church-Yard (London: John Van Vorst, 1836).

On loan from a private Sussex collection, arranged by Gorringes Fine Art Auctioneers, Lewes, East Sussex: Thomas Gray, Elegy written in a Country Church-Yard (London: John Van Vorst, 1836). Van Vorst (1804-98) was a highly commercially minded reprint publisher who specialised in part in illustrated works of natural history. He collaborated with John Martin (1791-1855) to produce an illustrated edition of Gray’s ‘Elegy’, with one illustration for each of the stanzas of the poem, each provided by a different artist. First published in 1834, the edition was reprinted in 1836. This copy, bound in red morocco by J. Mackenzie and Son, has Martin’s bookplate and contains correspondence with the dedicatee (Samuel Rogers). Bound into it are the designs used for seventeen of the engravings by those of the contributing artists who did not draw directly onto the wood blocks (George Barrett; Anthony Vandyke Copley; Fielding; George Cattermole; Thomas Stothard; Peter De Wint; Sir William Boxall; William Westall; Charles Landseer; John James Chalon; Richard Westall; John William Wright; Frank Howard).

Original artwork.

Engraved version.

The most important of these was John Constable (1776-1837), who was at work on his contribution to the book in August 1833 and supplied three designs for the first edition (stanzas III, V, and XI). The volume contains all three of his watercolours for these illustrations. It also contains a letter from Constable to Martin, dated 9 July 1835, in which he discusses further designs for this, the second edition, including an alternative view of the churchyard to the one reproduced on the title-page.

Detail of letter from John Constable.

Translations

-

Latin & Italian

Peterhouse, Ward Library, Pet.473.c.35: Elegia inglese di Signor Tommaso Gray sopra un cimitero di campagna (Padua: Giuseppe Comino, 1772). A Latin translation of the Elegy by Giovanni Costa and one in Italian by Giuseppe Gennari. Both versions were later reprinted and anthologised.

-

Greek & English

Peterhouse, Ward Library, Pet. 473.c.61: A parallel Greek and English printing of the ‘Elegy’ (London: J. Nichols, 1794), with the Greek version produced by Bowyer Edward Spark, bound with a second Greek version (London: Joseph Cooper, 1794), which was the work of Charles Coote (1761-1835). Two of half a dozen Greek versions printed in part for distribution by Cambridge booksellers between 1785 and 1795

-

Welsh

Peterhouse, Ward Library, Pet.473.c.95: Myfyrdod ar einioes ac angau, a ysgrifenwyd mewn mynwent yn y wlad, yn mrig yr hwyr, 2nd edition (Carmarthen: J. Evans, 1812). A translation of the ‘Elegy’ into Welsh by David Davis (1745-1827) of Castle Howel, first published in 1798.

-

Greek, Latin, German, Italian & French

Peterhouse, Ward Library, Pet.473.c.89: The polyglot version of Van Vorst’s edition of the ‘Elegy’, published in 1839. With translations of the poem in Greek (William Cooke), Latin (William Hildyard), German (Friedrich Wilhelm Gotter), Italian (Giuseppe Torelli), and French (Marie-Joseph Chénier). This edition cost 12s. when published in the original cloth.

-

Armenian

Peterhouse, Ward Library, Pet.473.c.82: Beauties of the English Poets (Venice [San Lazzaro]: Armenian Academy, 1852). This anthology of English poetry with facing page Armenian translation had its origins in Lord Byron’s visit to the Mekhitarist monastery on San Lazzaro in 1816. Selections from his poetry first appeared from the monks’ press in 1819, and in this edition are accompanied by Gray’s ‘Elegy’ and his ‘Ode on the Death of a Favourite Cat’, and poetry by Pope, Milton, and others.

-

Italian, French, German, Latin, Hebrew, Modern Greek

Peterhouse, Ward Library, Pet.473.c.60: L’Elegia di Tommaso Gray, sopra un cimitero di campagna (Verona: Tipografia Mainardi, 1817). This includes English and eight Italian versions of the ‘Elegy’, as well as two translations in French, two in German, four in Latin, one in Hebrew, and and one in modern Greek. The edition was limited to 350 copies.

The ‘Elegy’ inspiring artists

Many artists have drawn inspiration from the ‘Elegy’. The engravings for the ‘Elegy’ by Bentley were particularly striking and represented the origin of a long tradition of illustrating the poem.

Peterhouse, Ward Library, Pet.F.473.A.19: Designs by Mr. R. Bentley for Six Poems by Mr. T. Gray (London: R. Dodsley, 1753).

The engravings for the ‘Elegy’ were particularly striking and represented the origin of a long tradition of illustrating the poem.

Peterhouse, Ward Library, Pet.F.473.A.22: William Blake’s Water-Colour Designs for the Poems of Thomas Gray, edited by Geoffrey Keynes (London: Trianon Press, 1972).

One of the most famous series of illustrations were by William Blake. Shown here from a facsimile edition, Number 96 of 518 copies, sponsored by Paul Mellon, of a book that he owned containing 116 inlaid pages from Gray’s Poems (1790), illustrated by William Blake (1757-1827) in watercolour in 1797-8. John Flaxman had commissioned Blake to paint a series of watercolour illustrations as a birthday present for his wife, taking as a model the deluxe edition of Edward Young’s Night Thoughts, which Blake had illustrated for the bookseller Richard Edwards a few years before. Blake’s version of Gray was never intended for publication.

Detail of Blake’s illustration.

Blake inspired others like the sculptor, architect, and photographer Lucas who produced a series of 19 etchings for Gray’s ‘Elegy’ (dedicated to the banker Henry Merrik Hoare, September 1841) as well as Goldsmith’s Deserted Village in the same year.

Peterhouse, Ward Library, MS Lucas: Folio of 19 etchings for Gray’s ‘Elegy’ (dedicated to the banker Henry Merrik Hoare, September 1841) by Richard Cockle Lucas (1800-1883).

Details of Lucas’ etching.

20th Century & Later

In the twentieth century a number of women artists interpreted Grey’s ‘Elegy’ in woodcuts and engravings. One particularly evocative 1938 edition designed by Robert Ashwin Maynard and produced at his press at Alperton, Middlesex in 1500 copies (this is number 379) with illustrations by Agnes Miller Parker (1895-1980).

Peterhouse, Ward Library, Pet.473.c.56: Printed at the Raven Press for members of the Limited Editions Club in 1938, with an introduction by Sir Hugh Walpole.

Illustrations by Agnes Miller Parker.

Peterhouse, Ward Library, Pet.473.c.75. The Golden Cockerel Press edition of the ‘Elegy’ (London, 1946).

The Golden Cockerel Press edition of the ‘Elegy’ (London, 1946), produced by Christopher Sandford. Printed in Caslon Old Face by F.J. Newberry at the Chiswick Press (pressman: A. Curran). The edition consisted of 750 copies of which this was copy 31 (of 80 that were specially bound). Illustrated by Gwenda Morgan.

Wood engraving by Gwenda Morgan.

Peterhouse, Ward Library, 473 A.33: An Elegy written in a Country Churchyard (Market Drayton: Tern Press, 1995).

A more recent example of the ‘Elegy’ inspiring artists is seen here, the limited edition (number nine of fifteen copies) with watercolour paintings by Nicholas Parry (1937-2012), bound by Mary Parry. The Parrys began the Tern Press in 1973. Set in 36-point Garamond type and printed on Saunders mould-made paper, and originally priced at £1500.

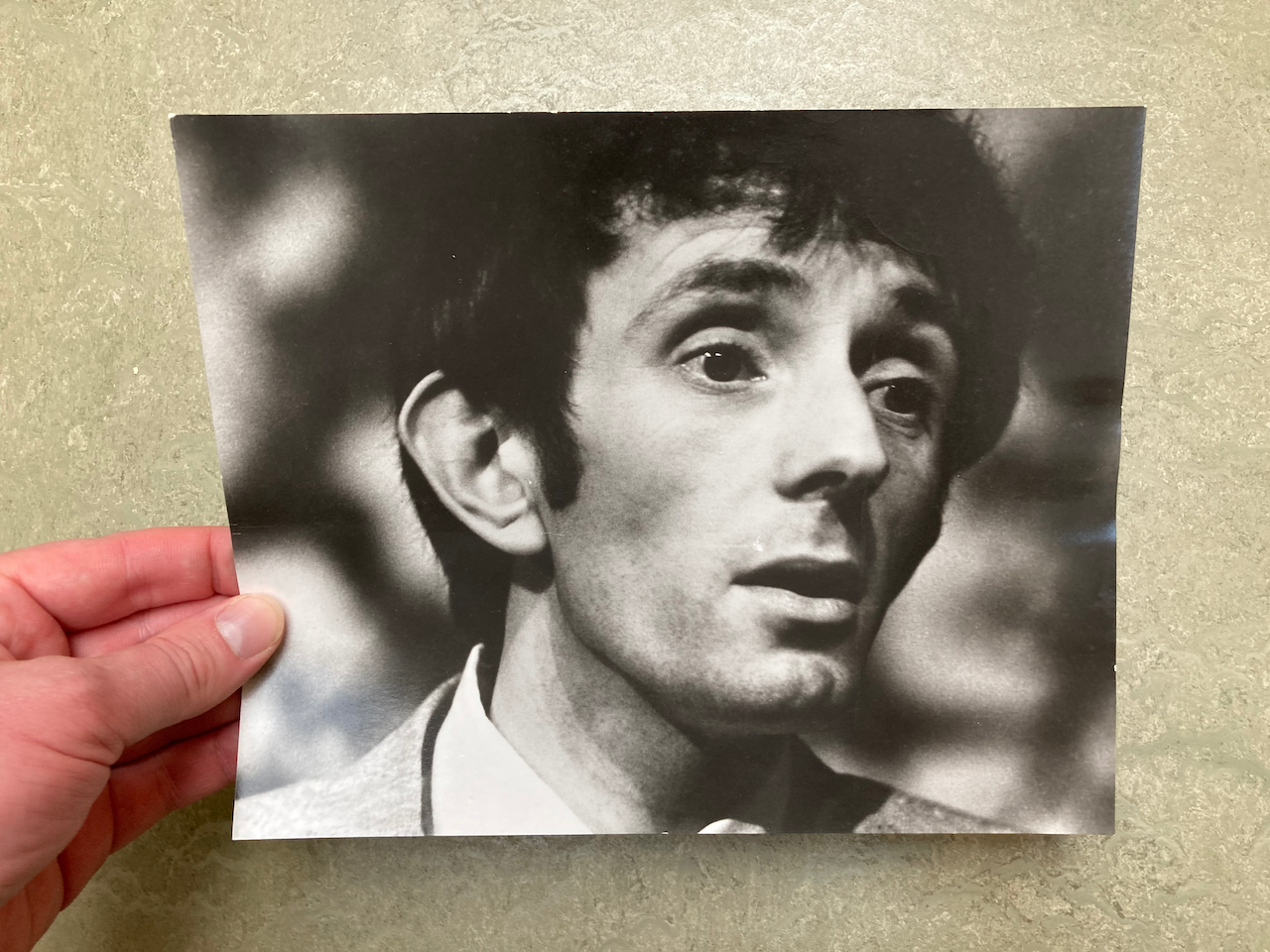

Performing the ‘Elegy’

Shown below are materials relating to the one-man show dedicated to readings from Thomas Gray’s poems and letters by Michael Burrell (1937-2014), who read English at Peterhouse from 1958. Burrell was largely responsible for organising the Gray bicentennial celebrations in 1971. His recording (Studio Republic) of the ‘Elegy’ has been widely reproduced and can be listened to above.

Michael Burrell

Items from the Burrell Collection

Varieties of the ‘Elegy’

GRAY IN CAMBRIDGE